Audiovisual piracy has established an infamous reputation as one of the most financially damaging issues facing the modern sports industry. Last year, a letter signed by various sports rights holders, urging the European Union to take action, claimed that piracy was costing them an estimated $28.3bn (€24.9bn) in new revenue each year. In fact, the totals may be higher, given that the figure was based on a 2021 study by Synamedia and Ampere Analysis.

It is certainly a problem of which LaLiga, which operates Spain’s top two football divisions, is all too aware.

Internal assessments detail that audiovisual piracy causes losses of between €600m and €700m per year to LaLiga clubs alone. This figure includes direct revenue leakage from illegal streaming, along with the erosion of rights value due to a reduced willingness to pay from broadcasters, and platforms exposed to piracy-heavy markets.

Understandably, it has therefore become a key issue for an entity that has made no secret of its grand ambitions to grow in influence and impact abroad as well as at home.

“Fighting audiovisual piracy is a top strategic and legal priority for LaLiga because it directly compromises the sustainability of our competition and the value of our audiovisual rights,” says Guillermo Rodríguez, head of operations for digital and audiovisual antifraud at LaLiga. “This is not just about protecting a commercial asset – it’s about defending the competitive integrity of Spanish professional football and ensuring a level playing field in the global market for sports broadcasting.”

To highlight the scale of the problem facing LaLiga, a 2025 report from the Live Content Coalition (LCC) found that in 2024 there were 10.8 million illegal sports streams detected in Europe, of which 81 per cent remained active throughout the event.

Rodríguez notes that only 2.7 per cent of the streams were disrupted within 30 minutes, which is viewed as the “critical window” for taking down live content. “These figures are staggering,” says Rodríguez. “They point to an ecosystem in which piracy is not an exception, but a parallel economy, professionalised and globalised.”

A model to follow

LaLiga has been one of the most proactive sports organisations when it comes to tackling the issue of piracy. By Rodríguez’s admission, LaLiga’s campaign has been “multi-faceted” and “legally grounded”. Instead of focusing solely on technology, LaLiga has prioritised legal action, judicial recognition and cross-border cooperation.

The campaign has been headed up by president Javier Tebas, a vocal critic of the likes of Google and Cloudflare, whose technology he has accused of enabling piracy.

Legal wins have provided essential foundations in LaLiga’s fight against piracy. In 2024, Spanish courts ruled in favour of the league’s position that infrastructure providers such as Cloudflare must be held accountable when their services are systematically used by illegal operators. Just weeks ago, this was backed again by the courts, enabling LaLiga to coordinate real-time actions with internet service providers, broadcasters and regulators to limit the availability of pirated matches.

“Spanish courts validated our capacity to implement dynamic blocking measures, which we manage in a surgical way to avoid the maximum collateral damages,” Rodríguez says. “This aligns with legal precedents also obtained by other leagues in Italy and France.

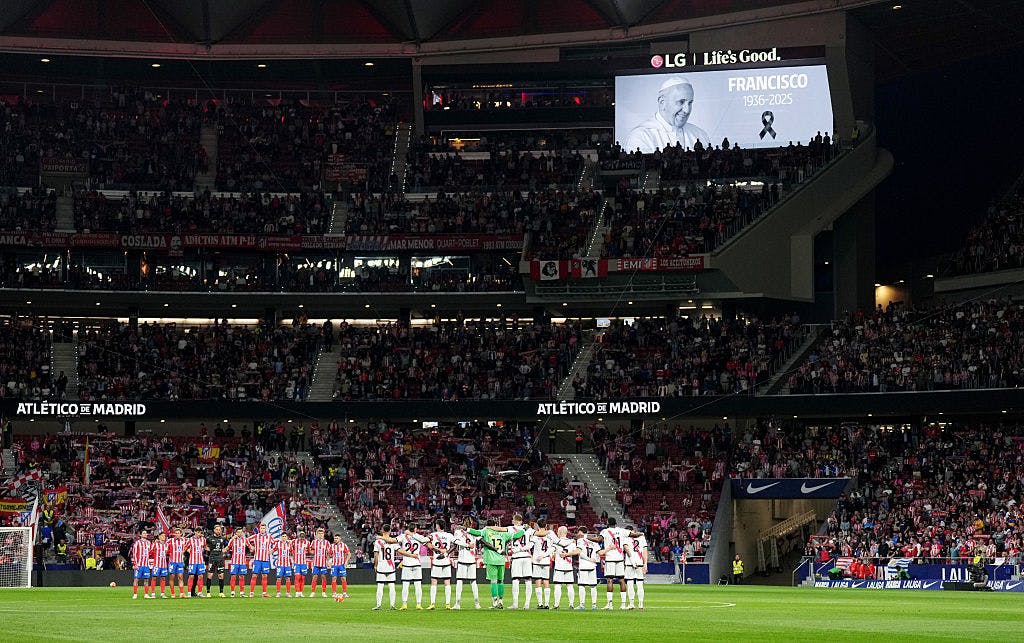

“We’ve also operated successfully in other territories. For example, in the hours leading up to the Madrid derby in October 2024, LaLiga deactivated the pirate IPTV platform Duckvision, one of the main distributors of illegal live content in Spain. The operation involved cooperation with cybercrime units, broadcasters and international partners.”

Judicial rulings empower LaLiga to coordinate blocking and enforcement efforts in collaboration with other broadcasters and technical partners. Rodríguez says that LaLiga’s joint enforcement actions with other rights-holders have allowed the league to block entire clusters of illegal pirate domains that previously escaped individual interventions.

The focus for LaLiga is on “strategic disruption” rather than isolated takedowns. In practice, this leads to the organisation identifying the so-called “technical core” of pirate networks, such as the advertising and payment infrastructures that sustain them, as well as the distribution channels.

“By acting under a unified legal mandate and with strategic partnerships in place, we have improved both the speed and impact of our interventions – and set a model for other competitions to follow,” Rodríguez says.

Operation Takedown

In years gone by, the main source of pirated content was streaming websites. However, in an evolving landscape, illegal IPTV boxes have becoming increasingly common in recent years.

Such boxes have dramatically increased the “complexity of enforcement”, Rodriguez says. With consumers able to purchase boxes for as little as €30 per year, piracy has never been so widespread.

Boxes are preconfigured with pirate apps, streaming protocols and automatic updates that allow pirates to shift servers or relaunch channels when old ones are taken down. They can be sold via online marketplaces, through social media or simply by word of mouth, with Rodríguez describing the IPTV market as a “full hardware-software ecosystem”.

Accordingly, LaLiga has adopted a multi-layered approach, treating contributors to the issue as “criminal enterprises”, Rodríguez says.

The servers behind the services, the financial intermediaries processing payments, the local resellers who distribute the boxes, and the networks – such as WhatsApp or Telegram – that provide customer support, as well as the distribution networks such as marketplaces or social media channels, are all investigated and scrutinised.

In 2024, LaLiga participated in Operation Takedown, coordinated by Europol, which dismantled a network serving over 22 million users across Europe. “This is the scale we’re dealing with – and the level of response required,” Rodríguez adds.

Economic damage

LaLiga’s stance on the issue is shared by other leagues, providing grounds for collaboration between natural industry rivals.

“We’re not talking about harmless tinkerers who crack a stream for their friends, but about gang-organised international crime, which is often linked to other illegal activities,” publicly stated Oliver Pribramsky, head of rights management, technologies and archives for the German Football League (DFL). “It’s about offences such as theft, copyright infringement or fraud and the associated economic damage for providers and the state, because the criminal networks don’t pay taxes either.”

Vincent Labrune, president of France’s Professional Football League (LFP), describes piracy as an “absolute emergency”, while Mark Lichtenhein, chairman of the Sports Rights Owners Coalition (SROC), believes it is the “biggest problem that sport rights owners have across the board”.

It is not only leagues and broadcasters that feel the impact of such large-scale piracy; clubs are also hit hard – particularly lower down the league ladder.

“When piracy eats into the value of audiovisual rights, it reduces the central income pool that is distributed among clubs,” Rodríguez says. “That has very tangible consequences: clubs invest less in player recruitment, academy systems, stadium improvements and community outreach.

“Over time, this creates a competitive imbalance not just within LaLiga, but between European leagues – as those with stronger enforcement benefit disproportionately. Piracy also affects strategic planning. Clubs cannot make long-term investments with confidence if their revenue is subject to erosion from illegal consumption – and for new investors, piracy is a red flag. It introduces legal and reputational risks that make clubs in piracy-heavy markets less attractive.”

Holding tech companies to account

LaLiga has not been shy in calling out the technology giants, and Rodríguez believes the role of such companies in the piracy issue has become “increasingly difficult to ignore”.

Although Google and other companies do not produce or host illegal content directly, Rodríguez states that they are often the “gateway” through which piracy becomes accessible to the public. “When these intermediaries fail to act swiftly or thoroughly, despite being notified, they become part of the problem,” he says.

In December, Tebas described Google and Cloudflare as “enablers” of the pirating of content from LaLiga.

“LaLiga does not take these claims lightly,” Rodríguez adds. “When we describe companies like Cloudflare or Google as enablers, we are pointing to very specific behaviours. These platforms – while not directly responsible for content – often provide technical infrastructure that allows piracy to flourish, even after being notified, profiting from illegal activities that take place thanks to its collaboration and using the legal clients as a barricade.”

Rodríguez cites a case opened by the Madrid Provincial Prosecutor’s Office in April 2025 against the developer of a piracy app called IPTVEXTREME, which was available for download via Google Play, as a pertinent and recent example. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, the app facilitated unauthorised access to high-value audiovisual content – including LaLiga matches – and operated using technologies such as M3U lists and APK codes.

According to Rodríguez, the case underlines the argument that Google Play acted as a necessary facilitator in the illicit distribution of intellectual property. He also notes that Cloudflare has “repeatedly been used” by pirate operators to hide server infrastructure and avoid enforcement.

Last year, a Spanish court ruled that services systematically used for piracy, even when technically neutral, must act once notified. This followed earlier rulings in Italy and France compelling Cloudflare to block domains and disclose the identities of repeat infringers.

“These platforms frequently claim to be helping rights-holders, but the reality is quite different,” Rodríguez says. “They continue to index pirate sites in their search engines, even after repeated notifications. They fail to remove or block piracy apps, some of which request abusive permissions that can compromise user privacy, access photo galleries, financial data, or even inject malware onto devices.

“Worse still, although their terms of service contain explicit commitments to protecting intellectual property, these are rarely enforced in practice. Known repeat infringers are allowed to return to the platform, over and over again, often using the same technical infrastructure.”

It is claimed that a lack of action on the part of such companies is telling.

“These platforms do not initiate legal proceedings against those who use their services to distribute or promote illegal content. This reflects a deep, structural tolerance for illicit activity that benefits their traffic, engagement, and ultimately, advertising revenues,” Rodríguez adds.

“Our position is clear: there is no excuse for inaction when the abuse is systematic, recurrent, and well-documented. Passive neutrality is no longer an acceptable stance. Global tech companies must stop hiding behind policies and start applying them.”

Rodriguez states that “there is a need for the industry to take this issue seriously, as the response is not being strong enough and there is a need for more awareness, investment and commitment from broadcasters, telco companies, leagues and other key stakeholders.”

Harnessing AI

This season, LaLiga is scaling its operational capacity “significantly” with the aim of increasing the volume and speed of live takedowns. LaLiga is also aiming to expand the reach of its blocking actions to more territories and languages, while consolidating new strategic legal cases.

Artificial intelligence (AI), as an increasingly prevalent tool across society at large as well as the sports industry, is already being harnessing by LaLiga in its fight against piracy.

The organisation is using AI to monitor domain registration patterns, track suspicious traffic behaviour, and assist in cross-referencing signals that may indicate the existence of an illegal distribution network. This capacity will allow the league to focus enforcement resources more effectively and adapt to piracy operators’ evolving techniques.

AI is also used to identify LaLiga content that is being distributed and streamed illegally on different platforms and services. Tebas has described AI as LaLiga’s “competitive edge in the digital fight for football’s value”, and this is a view shared by Rodríguez.

“AI is not replacing human judgement, but is amplifying our ability to act faster and more decisively – whether that’s taking down a domain 10 minutes before kick-off or identifying new nodes in an IPTV infrastructure before they gain traction,” he says. “In the coming seasons, we aim to deepen this integration, aligning AI intelligence with legal triggers, technical blocking systems, and collaborative enforcement across borders.

“What guides our strategy is not only a numerical target, but effectiveness and deterrence. Every intervention – whether it’s a platform shutdown before a major fixture, a successful court order against an intermediary, or a collaborative takedown with another rights-holder – is assessed not only on volume but on impact.

“This approach ensures that we focus our efforts where they hurt piracy most: distribution, infrastructure, and monetisation across different platforms and countries, targeting the core of the criminal structures that support piracy.”